The Story about the Flørli Power Plant.

“The steelworks that, we are happy to say, never came into being.”

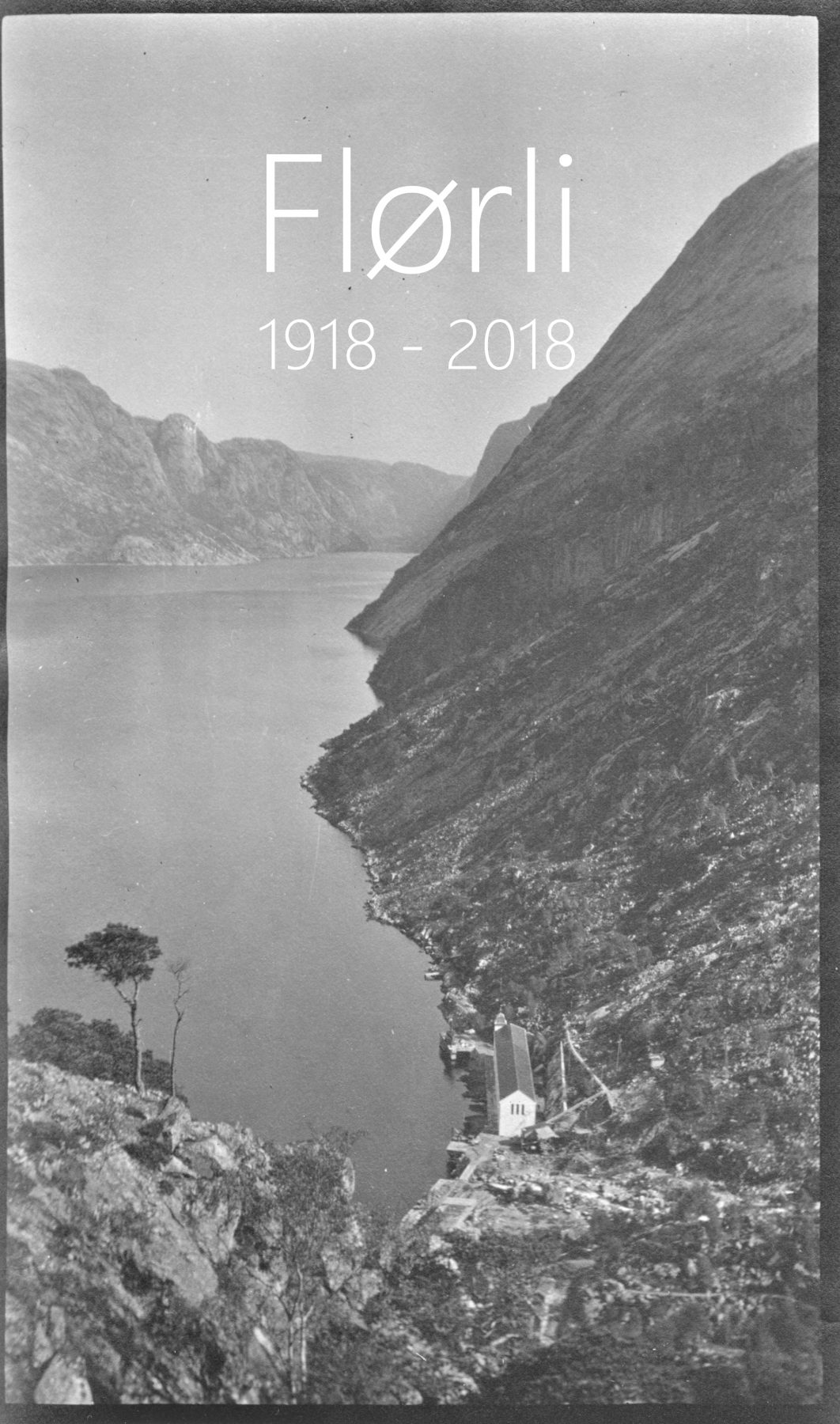

Flørli is a place where the conditions for hydropower production are very good. The fall from the lake Flørlivatnet to the sea level is 740 meters – the second highest fall ever built in Norway. Therefore, the property Flørli with surrounding mountain areas and lakes, was bought in 1914 for 16.000 crowns by a businessman from Stavanger, Einar Meling.

A/S Flørli Kraft- og Elektrosmelteverk was founded in 1916, with a share capital of one million crowns. A production of 12000 hp was planned by a hydropower station in Flørli and the electricity would be used by an accompanying steelworks that was to be constructed in Flørli as well. An agreement was made with Röchlingische Eisen- und Stahlwerke in Duisburg, Germany who would buy the steel for further processing.

A/S Flørli got a concession on the 16th of November, 1916. By then the building of the hydropower station had already started. Even though the building process went according to plan, the world situation changed dramatically. The Germans needed steel for arms production, but their warluck changed and the steel market collapsed. The Lysefjord therefore never got its steelworks – and we should probably be glad for that today.

The Building Period

Even though the conditions for hydroelectricity production in Flørli were favourable, the building of dams and a water pipeline in this area was to cost much toil and sweat. A lot of equipment had to be brought up to the lake, 740 meters above the sea level. That job had to be done by human power as the terrain was largely too steep for horses. A year after the work had started, rails were laid for a trolley to bring equipment and people from the fjord to the mountain top. Many tales about brave deeds date from this period. Well-known is a story about a local called Nils Helmikstøl who is said to have carried 135 kilo uphill on his back! The average payload for a man was 80 kilo – also beyond imagination to most people today.

A little society is created at Flørli

The first things needed at Flørli were a solid quay and a smaller hydropower plant to provide energy for the construction works. As time went on, provisional lodgings were put up by the fjord as well as on the mountain. Half-way up the hill is Flørlistølen. This came to be a base or starting point for those who brought materials and equipment by horse up to Flørlivatnet. The building of the dams on the mountain took a lot of time and similar efforts were put into the construction of the hydropower station and the stone foundations by the fjord that were being laid for the steelworks. All simultaneously.

In 1916 the number of people employed at the construction works was 119. By the summer of 1917 the working force was at its height: 142 persons were at that time employed at the construction works. Many of the workers lived in the small lodgings, some together with their family. The conditions must have been difficult both for the children and for the grown-ups. One knows that 47 persons were living in 12 small rooms. Eventually, Flørli got its own shop, a post service, a school, a telephone service and a doctor’s office – much of it after the initial construction period though.

The water pipeline

From the power plant by the fjord up to the dam in Ternevatnet a water pipeline was to be built. The pipe was to be buried in concrete, fastened to the rock. In order to carry out this work rails were laid up the hill, and a powerful winch pulled trolleys uphill. In this connection many problems turned up. On one occasion the cable snapped, causing a trolley with nine persons on it to rush downhill at full speed. The men managed to jump off in time, but it is said that from that day on some of the workers refused to mount the trolley. Shortly after construction, a fissure in the pipe caused a catastrophic flood and rock slide damaging part of the power station before water was finally shut off. As a maintenance access, wooden stairs were built along the rails. Today the stairs consist of 4444 steps, being the longest of its kind in the world.

Fight against the elements

The construction work was carried out continuously throughout the year, but in winter snow created big problems. After Easter 1917 the weather was so bad in the mountains that work could be done just 3 or 4 days a week. During the worst periods the men had to stay in their sheds ten days in a row. This meant economic difficulties for those men paid by the hour. The result was that the employer agreed to pay 5 crowns a day during such idle periods.

In February 1918 there was an awfully strong snow storm which ruined the electric lines. By Lille Flørlivatnet a snow drift, eight meters thick over the shed roof caused the roof to give in. The men had to move in the middle of the night to another shed, and to get out from there they had to dig their way through the snow drift. During the long winter some working teams were fully occupied shuffling snow!

Despite harsh and dangerous working conditions, no one died during the construction of Flørli.

The Flørli power station started production in summer 1918. Production was ceased in 1999 and a new, automated station inside the mountain was opened in the year 2000. Flørli celebrated its hundred year jubilee in 2018.

Electricity to Stavanger

In 1918 all electricity produced in Flørli was sold to Stavanger Elektrisitetsverk, and the the Flørli company hoped to earn quite a lot of money from their power production. This, however, turned out not to be the case. Because of sudden changes on the finance market the production costs were higher than expected. The company got new loans, but they also meant new costs. In 1928 the debts amounted to 5,7 million crowns, and the company was in fact bankrupt. The banks which had leant the money, were themselves in deep trouble.

In 1925 Flørli A/S wanted to sell their industry to the city of Stavanger. The times were bad, however, and agreement was not achieved until two years later. In 1927 the power plant was eventually sold to Stavanger Elektrisitetsverk for 3,75 million crowns, which was about half the sum originally suggested. For 25 years to come, then, Flørli was to be Stavangers most important source of energy until an even larger power station in Lysebotn was constructed shortly after the war.